- Home

- Jones, Sherry

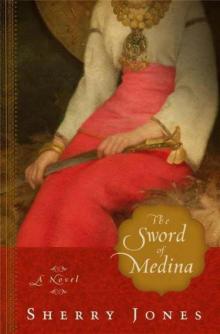

The Sword Of Medina

The Sword Of Medina Read online

The Sword of Medina

A Novel

The Sword of Medina

A Novel

SHERRY JONES

The Sword of Medina is a work of fiction. All characters, with the exception of well-known historical figures herein, and all dialogue, are products of the author’s imagination.

Copyright © 2009 by Sherry Jones

FIRST EDITION

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover Image: An Arab Girl holding a Sword, a Shield Behind her by Paul Desire Trouillebert (1829-1900) Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/The Bridgeman Art Library

Map: Kat Bennett, 360Geographics

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Sherry, 1961-

The sword of Medina : a novel / Sherry Jones.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8253-0520-7

1. ‘A’ishah, ca. 614-678--Fiction. 2. ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, Caliph, 600 (ca.)-661--Fiction. 3. Muhammad, Prophet, d. 632--Fiction. 4. Muslims--History--Fiction. 5. Islam--History--Fiction. I. Title.

PS3610.O6285S96 2009

813’.6--dc22

2009016281

Published in the United States by Beaufort Books, New York

www.beaufortbooks.com

Distributed by Midpoint Trade Books, New York

www.midpointtrade.com

Printed in the United States of America

For Michael, who reminds me every day that love is a verb.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Natasha Kern, literary agent extraordinaire and very dear friend, and my publishers, editors, and publicists around the world for their support during the most trying of times, especially Eric Kampmann and Erin Smith at Beaufort Books and publicist Michael Wright. Special thanks for editing help goes to Carol Craig and Trish Hoard, both of whom have helped make me a better writer, to Margot Atwell at Beaufort Books and Meike Frese at Pendo Verlag, who made this a better book, and to Richard Myers, Todd Mowbray, and the many other friends and fans who have encouraged me to persevere.

THE FIRST RIGHTLY GUIDED CALIPH

ABU BAKR

632–634 A.D.

A’isha

Muhammad is dead.

In the heart-skip between waking and sleep, I remembered the awful truth. The long, slow exhale—my husband’s final sigh—the evening before. His head pressed to my shuddering heart. His stiffened face, as if turned to stone, when I’d laid him in our bed. Now he lay beneath me, buried in my room, the fresh earth moistened by my tears. Exhausted after the long night, I’d fallen asleep atop his grave. Not even the call to morning prayer had roused me. Now a hand was shaking me awake, and Hafsa’s voice, urgent. A riot in the street. Your father. A’isha, you must come now.

I could still hear the thunder and crash of my dreams. The images were already dissolving like mist burned away by the sun, but I vaguely recalled a splitting—was it the Ka’ba, our sacred temple, cracking in two? I sprang from my bed, my pulse fluttering, and shrugged off my nightmare, leaving it on the dirt floor. Holding our wrappers close about our faces, I and Hafsa ran into the small, cool mosque adjoining my hut, our bare feet kicking up dust, then out the mosque’s front door and into Medina’s main street. There a stampede of men brandished blades and cried, “Yaa Abu Bakr! Yaa khalifa! Praise to al-Lah for our new leader!” My heart’s skitter slowed as I realized that abi wasn’t in danger. The opposite was true: While I’d slept, my father, Abu Bakr, had won the heart of Medina.

Hours earlier, just after Muhammad’s death, I’d gone to see abi in the town hall, where the men of Medina had gathered to choose the successor to my husband, the Prophet of al-Lah and the leader of our community. My father and his friends had learned of the meeting and hastened away to join it, leaving Muhammad’s body unattended in my hut. I’d followed close behind, then returned to discover the terrible deed Muhammad’s cousin Ali had committed, with his uncle urging him on.

I’d raced back to tell abi, who’d listened with his air of infinite calm as I’d described the digging of the grave in my bedroom floor while I’d listened outside the door; the washing of Muhammad’s body while he was still clothed; the murmured assurances from al-Abbas, Ali’s uncle, that this secret burial was necessary. If there were a public ceremony, he’d pointed out, my father, Muhammad’s closest friend and advisor, would perform the prayer. That would seal him once and for all as the Prophet’s successor, al-Abbas had said. Ali wanted the khalifa for himself. He and his uncle had hoped to keep my father from becoming the leader of Muslims. Today, I could see that their efforts had failed.

Men in white—Muhammad’s color—and women whose wrappers sheltered their heads from the sun cheered and leaped and sang and whooped: “Come all, come! Pledge allegiance to the new khalifa, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, the Truthful.” After watching Muhammad’s slow death from Medina fever I’d thought that my well was empty of tears, but now water flowed again at the sight of my father floating in the people’s midst, carried aloft like a hero or king, his own eyes brimming, delaying his grief for the sake of the umma, the community of Believers.

I flattened myself against the building to avoid being trampled. But the torrent turned before it reached me and roiled into the mosque: Aws and Khazraj, the main tribes of Medina; emigrants from Mecca, our homeland, and elsewhere who’d come to Medina to escape persecution; and Bedouins of the desert, who’d loved Muhammad because he’d treated them as equals. Behind them marched Companions to Muhammad, including the stern Umar, his dark face forcing a heartsick smile, and Abu Ubaydah, whose eyes held worry even as he hoisted his sword and shouted abi’s name.

Once they were all inside—by al-Lah, I never saw so many men squeeze into that tiny mosque!—I slipped in, also, made invisible by the wrapper I wore over my hair and face. The crowd set abi on the date-palm stump where Muhammad had stood countless times to lead our umma in prayer, and tears began to pour in earnest down my father’s cheeks. My stomach twisted as I thought again of my husband’s death the night before, his head on my breast; his sword in my hand, bequeathed to me; his dying command to use it in the jihad to come. He’d known I would honor his request, for he’d taught me how to fight and he’d witnessed my bravery on the battlefield. Recalling what had followed—Ali’s wicked deed—I cried anew—not only from sorrow, but also from outrage over the funeral we’d all been deprived of.

“My dear brothers,” my father’s voice sounded gargled and torn, as though his throat had been cut, “although I am unworthy to stand on our Prophet’s pulpit, I humbly thank you for your trust.”

From the rooftop rang the muezzin’s call to worship, summoning all Muslims to pledge their allegiance. In the doorway I spied the fat, bald-headed al-Abbas lurking like a spy in the shadows. Revulsion sent me out to the courtyard where my sister-wives clustered in the mosque’s entryway and watched the goings-on.

“Everyone seems so happy, all of a sudden,” drawled Raihana, the Jewess, her haunting, houri eyes turning down at the corners. She’d been a gift to Muhammad from his men, a captured princess. Our warriors had killed all the men of her tribe after their leaders had tried to assassinate Muhammad, and her resentment over the deaths of her husband and sons had given her a bitter tongue. “Don’t tell me another prophet has risen from the dead.”

“Do Jews believe in resurrection now?” Hafsa arched one of her famous flying eyebrows. She’d never believed in Raihana’s conversion to islam; like her father, Umar, she was skeptical about everything.

Unlike Umar, however, she possessed a keen sense of humor. “By al-Lah, soon you’ll be saying you believe in prophets, also!”

“Girls, this is no time for making jokes.” Superstitious old Sawdah, married to bring up Muhammad’s daughters but a mother to us all, gripped her evil-eye amulet so tightly I thought she’d strangle herself. “The Prophet is not even buried yet.”

“Actually, he is buried,” I said. My sister-wives turned their faces to me, open-mouthed—except for Ramlah, who laughed.

“Let me guess: Al-Abbas had a hand in it, did he not?” She showed her large teeth. “The man knows no limit to his ambition. Yet he certainly did not dirty his own hands. His spineless nephew Ali did the digging, I wager.”

I was tempted to point out that, as far as ambition was concerned, Ramlah’s father had set the example for all. Abu Sufyan, leader of the Meccan Quraysh tribe, had tried to kill Muhammad many times, jealous of his growing influence. Although Muhammad had married the daughter in effort to win the allegiance of the father, Abu Sufyan had been stubborn. He’d continued to send assassins to the mosque until, at last, he’d been forced to convert to islam—by the tip of Ali’s sword pressing into his neck. Ramlah had scorned Ali ever since, which made me feel almost tolerant toward her.

Maymunah, al-Abbas’s daughter—Ali’s cousin—didn’t bother to hold her tongue. “Yaa Ramlah, when you criticize Ali, it is the Prophet you denigrate,” she said, her billowing black hair making her look like a storm cloud. “He loved Ali as a son. And as the father to Muhammad’s only male heirs, Ali has a right to succeed him.”

“Yet we cannot ignore the desires of Quraysh,” the elegant, fair-skinned Umm Salama said in the measured tones that marked her as a member of the Qurayshi elite. Beautiful and aristocratic, she’d been a widow when Muhammad had proposed to her—three times. “Quraysh is the most powerful tribe in all of Hijaz. Would they support a leader from the Hashim clan?”

“Muhammad was a Hashimite,” Maymunah reminded her.

“But God spoke through Muhammad,” Ramlah said. “Has anyone heard revelations from the mouth of Ali?”

“Some of the Bedouin tribes might resist Ali’s rule,” Juwairriyah said, surprising me with her tinkling-bell voice, so rarely heard. She’d been a member of a Bedouin tribe—another enslaved princess—before marrying Muhammad in exchange for her freedom. “Passing the khalifa to the male heir would look too much like a monarchy. No Bedouin would ever serve a king.”

“As for me, I don’t care about any of this,” Zaynab said in a choked voice. My fiercest rival for Muhammad’s affection and for leadership of the harim, Zaynab was normally a fiery competitor who’d displayed her beauty and her passion for Muhammad as if she were a bird of paradise and the rest of us were mere chickens. Today, though, her curly hair was frizzled and matted, as if she had not combed it in weeks, and her tawny eyes were swollen and red-rimmed. She looked the way I felt.

“Muhammad is dead,” she said. Her face seemed to slide downward before she pressed her hands against her cheeks. “He was . . . the greatest of men . . . and he is gone from us. Gone! By al-Lah, how can you argue over the khalifa when we will not see his smile in this world again?”

Her accusation silenced us. Umm Salama folded her arms around the sobbing Zaynab and led her back to her hut while the sister-wives hung their heads in shame—except for me. I watched Zaynab walk away with a yearning to join her, to bury my face in my hands and succumb to the anguish of losing Muhammad. By al-Lah, wasn’t my grief greater than hers? Hadn’t Muhammad loved me best of all his wives? He’d known me all my life, married me when I was only nine, and raised me as a father—at first. Then, later, I opened his eyes to the woman I’d become, and his love had changed, deepened, until our hearts had beat as one.

Soon, I hoped, I’d be able to rest and grieve for my habib, my beloved. It seemed there would be no jihad, no struggle, for me to worry about. Ali and al-Abbas’s treacherous attempt to stop my father had failed. Abu Bakr was the khalifa now, and they could only accept it.

Before any of us could speak again, the thumps and slaps of one thousand men and women prostrating themselves arose from the mosque like the sound of a great beating heart. We sister-wives stepped into the cramped, square room and dropped to our knees. The pungent tang of unwashed bodies mingled with the perfumes used to mask their odors, sandalwood and myrrh and clove and sweat.

“Hail, khalifat rasul al-Lah,” the crowd proclaimed, naming my father “successor to the Prophet of God.” My heart panged as I noted the sadness creasing abi’s face, making him appear as old as the tree stump under his feet. This was not the way he’d wanted to pass the hours after the death of his bosom friend.

Ali, I suspected, was even more unhappy. He and al-Abbas had hoped Ali would be in my father’s place right now. Instead, they had to kneel in the dirt with the rest of Medina to pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr, Ali’s longtime rival, the man the Believers had chosen. Eager to see Ali humiliated, I looked around me, peered into every corner, scanned every bent head. The crude little mosque was dark, with its mud-brick walls and date-palm-frond roof dappling light. Men and women crammed the room as full as sheep in a pen. Even so, I would have seen Ali. I would have known his hair the color of wheat, his tunic cut low at the back of his neck, his narrow face with the upper lip that seemed always to curl as if he smelled something rotten. As the service ended, I scrutinized every face, disbelieving. Ali wasn’t here! But Umar was—and he, for one, was not surprised.

“Ali’s arrogance knows no bounds, as usual,” the severe, pock-faced Umar grumbled to my father as I approached the tree stump where he and abi stood. “By al-Lah! I will humble him this day.” Umar yanked his sword from the sheath under his arm and leapt to the floor, landing beside me but pretending, as usual, that I wasn’t there.

Behind us the crowd was beginning to disperse, women and children wandering out into the street, heading for home. Others, mostly men, clustered near the doorway, talking and glancing at us.

“Take care, yaa Umar,” my father said. “Shedding Ali’s blood would only enrage his supporters against us, and divide islam.”

“The sword is the only language Ali understands.” Umar turned toward the front door.

“That may be so,” my father said in his calm voice, “but I cannot allow you to confront him with that weapon. Muhammad loved Ali. They were cousins, and Muhammad raised him as a son. He married Ali to his daughter. He would not like to see us threatening him now.”

“Abi speaks truly, yaa Umar,” I said. “Besides, we don’t want Ali to say we forced him to pledge his allegiance. He’d use it as an excuse to oppose my father.”

Umar glowered at me, enraged to hear a woman contradicting him—in spite of the fact that Muhammad had turned to me for advice many times. My father smiled and held out his hand to pull me up onto the stump. There we stood, side by side, with Umar spluttering at our feet.

“I agree with A’isha,” abi said. “If you want to deal with Ali, please do so. But do not carry weapons to his home.”

“But—Ali will slice me in two!” Umar said.

My cousin Talha ran in, his handsome face flushed under his red-brown beard. “Yaa Abu Bakr, your son-in-law al-Zubayr is shouting from the window of Ali’s home that you have stolen the khalifa.”

“Stolen?” Abi’s bushy eyebrows flew upward.

Wanting to reassure him—my father was a sensitive man—I nudged abi with my elbow. “How could you steal the khalifa when it was given to you?” I said to him. “Al-Zubayr is only jealous.”

“Does he want the position for himself?” My father shook his head. “Al-Zubayr is an ambitious man, but—to follow in Muhammad’s footsteps?”

Talha grinned. “Al-Zubayr doesn’t want the khalifa. He wants his cousin, Ali, in the position.”

My laugh rang harsh. “Ali doesn’t quit, does he?”

“Al-Zubayr and Ali say they’ll die before they pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr,” Talha said.

Umar hoisted his sword. “By al-Lah! I will be the one to fulfill their prophecy.”

“Take heed, Umar,” my father said. “I forbid you to carry a blade to the home of Ali.”

The arm carrying Umar’s sword fell limply to his side. He shook his head, mumbling. I held my breath, wondering if Umar would defy my father and undo everything the two of them had accomplished. Then, to my relief, Umar sheathed his blade.

“Hearing is obeying, yaa khalifa.” With a gleam in his eye, he pulled a bullwhip from his belt.

“By al-Lah, here is all I need to do my work.” His laugh cracked as he snapped the whip in my direction, making me flinch. “With this, I will have no trouble beating any rebels into submission—or strangling the defiance from their misguided throats.”

♦

As Umar, Talha, and a growing mob from the mosque tramped down the street to Ali’s house, I fled through winding alleys to my sister Asma’s home—and found it empty. One of her sister-wives, a small woman with a frightened expression, shook her head when I asked where they’d gone. “Al-Zubayr dragged her away, and the boy Abdallah also. Al-Zubayr was shouting, ‘I don’t care if Abu Bakr is your father! You will not pledge allegiance to that traitor.’” I left her in a hurry, worry and fear clashing like swords about my head.

Asma and little Abdallah taken to Ali’s! Al-Zubayr was using my sister. My father would never allow anyone to attack the house if he knew his eldest daughter and his only grandson were inside. Yet I’d heard Umar mention setting Ali’s house on fire as he’d stormed away. Foreboding seized my chest as I fled back down the twisting path to the main road, thanking God for my father’s ban on swords and daggers. Please, al-Lah, keep my sister and nephew safe from harm.

The crowd of men in front of Ali’s home was as dense as if they were still hemmed in by the walls of the mosque. Shouts and threats punctured the air like the barks of dogs, and despite abi’s prohibition I spied flashes of blade in the mid-morning sun. Wanting to avoid being seen by Umar—who would order me back to the mosque—I clambered over the courtyard wall and spied Asma through a rear window. She was huddled on the floor with Abdallah in her arms, holding him fast while he squirmed and protested that he wanted to join his abi.

The Jewel Of Medina

The Jewel Of Medina The Sword Of Medina

The Sword Of Medina Four Sisters, All Queens

Four Sisters, All Queens